Rule of 40 📐

Measure them with the right ruler; a good tool to have in the toolbox

This isn’t the first time this happens.

I’m working on an article, it’s sitting in my drafts needing a few more adjustments before posting, and someone beats me to the punch.

In recent reporting calls, I’ve heard a number of CEOs mention the rule of 40. That might be why Claude Walker wrote a great article about it only a few days ago.

If you haven’t done so already, go ahead and read his post first. We’re both coming at it from slightly different angles, so hopefully you get something valuable from both our opinions.

Origin

There are lots of concepts from the world of Venture Capitalists that are useful to us as listed investors.

One such example is the rule of 40 (which was originally coined as ‘the rule of 40%’).

VCs started talking about this in the early 2000s as Saas was starting to eat the world in Silicon Valley, and growth became the centrepiece of every investment thesis.

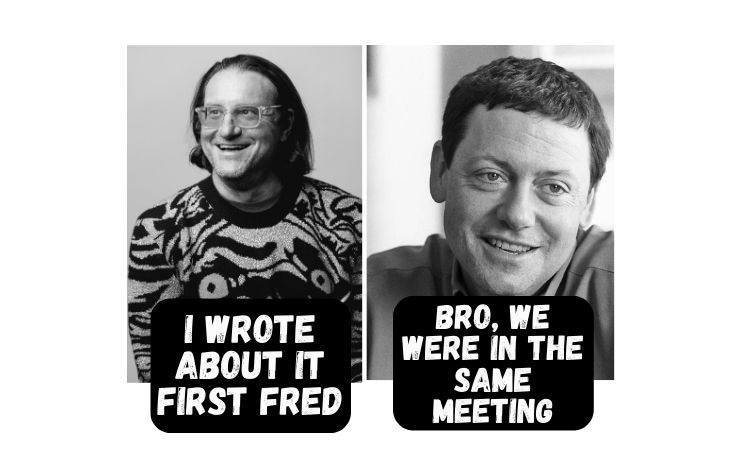

The idea was popularised and spread to the wider public when two of the godfathers in the VC industry published their respective blog posts on this in 2015:

The story goes that both Brad and Fred were at the same board meeting, when a late-stage investor explained the rule to them for the first time. It was simple and powerful enough that they both felt compelled to write about it at the time.

I have never seen growth and profitability so nicely tied together in a simple rule like this.

I’ve always felt intuitively that it’s OK to lose money if you are growing fast, and you must make money, and increasing amounts of it, as your growth slows.

Now there’s a formula for that instinct. And I like that very much.

Thanks Brad for posting it.

-Fred Wilson (the guy on the left)

Since, plenty of investors and VCs have written about what the rule is and how to apply it.

Given the concept is primarily VC focused, today I attempt to offer adaptions that make it more relevant to the public investor.

The Rule of 40

The rule of 40 is simple:

Your annual revenue growth rate + your margins should equal 40%

Here are 3 scenario examples:

If you are growing 40% year over year (YoY), you should be breaking even

If you are growing 20% YoY, you should have 20% margins

If you are growing 60% YoY, you can burn 20% margins (-20%).

Now, there’s a little bit of complexity beneath the hood.

Whilst growth rate should be easy to gather, what margins are we talking about here?

Contribution margins? EBITDA margins? GAAP Profitability margins? FCF margins?

I had a longer section answering this question, which I shrank down considerably. I think Claude does a fine job of answering it concisely, just read his answer.

But first, let’s talk about why I like it.

Reasons why I like it 👍

There are plenty of reasons why I like the rule of 40. Here they are:

1. It’s dead simple to use. Like you, I use other, more complicated formulas, which I will share in this blog, but the Rule of 40 is a good place to start. No calculators needed. It’s so simple your mom should be able to use it. No offence to your mom btw, not saying she’s simple.

2. It’s easy to track over time. The rule of 40 isn’t a static number. Every reporting season offers a new landing spot against the rule. Tracking it over time offers a lens to level the playing as field as companies transition to profitability.

3. It helps you eliminate quickly. So much of investing is ruling out companies that are not good enough for you to spend time researching (yet). It’s important to underline here that I don’t mean to say that anything below 40 should be discounted, far from that, but that if the numbers are quite appalling (which happens often), then perhaps discounting for now, and tuning in later makes the most sense.

4. It combines (arguably) the two most powerful metrics; growth and margins. Although if I could, I would overweight growth and underweight margins for earlier stage companies. More on this later.

The metrics to use 🧩

Ultimately adaptations are needed from you to decide on which metrics you pick to put into the rule. The idea is to stick to the same metrics for individual companies, else you won’t be able to build an accurate picture of their direction over time.

Metric #1 : Growth ⛰️

For a traditional business it may seem logical to pick revenue growth, but for early stage software businesses, revenue may not be the most accurate view of their traction.

In many cases, there are 2 reasons why I prefer annual recurring revenue (ARR) as a metric to revenue.

The first is that ARR measures the software piece, and excludes your one time fees, which do not scale overtime. So having a view only on ARR offers a slightly better window into the future.

Secondly, young, fast growers are typically signing contracts faster than they can implement them. This means you might find ARR growing faster than revenue can be recognised.(In the low multiples crew, I explain why it’s important to keep tabs on gross profit ARR).

One thing to be mindful of is the difference between Contracted ARR (CARR), and ARR. Some companies have a challenge of converting contract revenue into implement revenue (ref my Pointerra comments here). This exposes risks and limitations when using CARR as opposed to ARR.

Metric #2: Margins 🤏

Initially, the section I had dedicated to answering this question was much longer. I think Claude does a fine job of answering it concisely, just read his answer.

I tend to agree with Claude that the best margin is free cash flow. Why? Well, cash flow is ultimately what determines the value of a company. I slightly disagree with Claude and Munger (yeah, I know…) that EBITDA is bullshit. I explain why below.

The problem we have as early stage investors though is that the free cash flow margins of today may not accurately represent what the company can achieve once it grows to a certain size. This is why EBITDA is acceptable, but only for a certain period in a company’s growth. Not for 10 years.

This is partly why it’s so hard to value companies that are burning cash. You could also be asking yourselves if they’re selling $1 for 90c, or if there’s something truly special happening that needs to get to distribution before the gorillas can get to innovation.

Brad Feld’s comments on this are:

Profit is harder to define. Are we talking about EBITDA, Operating Income, Net Income, Free Cash Flow, Cash Flow or something else?

I prefer to use EBITDA here as the baseline and then back test with the other percentages.

If you are running on AWS or the cloud, this should be pretty simple and consistent. However, if you are running your own infrastructure, your EBITDA, Operating Income and Free Cash Flow will diverge from your Net Income and Cash Flow because of equipment purchases, debt to finance them, or lease expense.

So you have to be precise here with which number you are using and “it’ll depend” based on how your SaaS infrastructure works.

The important point to remember in my mind is:

Use the same margin for the same company and track it overtime.

If you compare 2 software companies against one another and you use EBITDA, you’ll have to dig into the EBITDA to see if one of those companies capitalises software development costs.

Software development cost is 100% real cost. There’s no way you can continue to grow and sell subscriptions to your software unless you continue to improve it overtime.

The rule of 40 - v2.0

When companies are early in their journey, the view on margins is slightly flawed.

The signs of operational leverage are still quite far away, and often impossible to pick up for the casual observer.

That why I propose a slightly adapted version of the rule, where we overweight growth, and underweight margins.

I propose:

Increase growth weighting by 1/3

Decrease margin weighting by 1/3

Why 33%? Well, 50% just seems like too much; like it’s diluting the power of principle too far. 33% seems just about right.

Rule of 40, 2.0:

Your annual revenue growth rate (multiplied by 1.33) +

your margins (multiplied by 0.66)

should equal 40%

Let’s see how this comes into play by putting both into practice from recent reports.

Putting into practice :

#1- Catapult Group (CAT.ASX)

Catapult have just recently reported full year results, and whilst the results were mixed, the market response as been very positive. Expectations were low prior to the release, and a strong second half showed promising signs of a potentially brighter future, hence a re-rate in the stock.

Catapult is interesting to look at with the rule of 40, because I’ve heard the leadership team on multiple occasions mention they use the rule of 40 to guide their decisions.

Revenue Growth

Here’s what they show in the slide deck for their revenue growth

Top line growth suggests 13% growth ($87.7M / $77M), but in reference to my point above, let’s take software revenue growth on the basis that this is what we really care about, and we know this is were the company’s efforts are going.

As the graph shows, on CC, this growth comes in at 21.8% ($70.5M / $57.9M)

Margins

Given these were full year results, Catapult does offer us EBITDA margins. Full year EBITDA margins came in at -13.1%.

CAT’s Rule of 40 on this basis: 21.8 - 13.1 = 8.7

Now, this is far from great.

But, let’s say we believe their narrative on the turnaround being in the works. This means we’ll accept the margins of second half as the a more accurate, true margin.

Margins in H2 were 5.1%. Let’s plug this in:

CAT’s Rule of 40 (using H2 numbers) on this basis: 21.8 + 5.1 = 26.9

Whilst much better, there remains a gap between 26.9 and 40.

Given it seems unlikely to me that they will be able to increase their growth rate, Catapult would have to make up this gap by increasing their margins. Can they get to 20% margins in the future? Well, according to them that’s possible, but I’ll have to see it to believe it.

If we used the v.2.0 version of the rule. Here’s what we get:

CAT’s Rule of 40 v.2.0 (using H2 numbers)

21.8 * 1.33 = 29

5.1 * 0.66 = 3.36

29 + 3.36 = 32.36

So, all in all, a company’s leadership that talks a lot about the rule of 40, doesn’t necessarily mean they meet the rule of 40.

To add to this point, one might further argue that Catapult actually capitalise some costs that are very real. Looking at the financial statement, you would notice depreciation and amortisation is $US 20.596M. That’s not a small figure. Why is it so large? A large part of this comes from their wearable demo units (~$6M). That’s something that seems very necessary for the business to continue to run.

#2 - Gentrack Group Ltd (GTK.ASX)

Another company who’s on a recent tear is Gentrack. The company had hit a few bumps in the road in early 2020 when the pandemic hit their target market considerably (they sell to utilities and airports), and they retracted guidance.

In the last 2 years a nicely executed turnaround has taken place, and recent results have been very strong, let’s look at it.

ARR excl. insolvent customers at $45.4M - growth of 37%

EBITDA at $16m (All R&D investment expensed in the period) - EBITDA margin at 18.9%

Gentrack’s Rule of 40 on this basis: 37 + 18.9 = 55.9

Wow, great result right?

Yes certainly, but this is where extrapolation can become dangerous.

Firstly, they included insolvent customers. If we account for insolvent customers, then growth comes closer to ~28%. This bring the rule of 40 number to 46.9.

Secondly, referring to my earlier point above, it appears Gentrack may have graduated to a point where we can evaluate them on the basis of profit margins now. This goes to the point of using the right margins for the right stage of the business.

If we use their profit margins, which are at around ~9%

And the real growth rate, around ~28%

Then the rule of 40 comes in at 37

If we plug that in to the V2.0 version, we get almost exactly the same number

Still, that remains very impressive. Here, one should track it overtime in the next few years to see if this trend can continue. That’s where the beauty of the rule comes in.

#3 - Catapult vs. Gentrack

What conclusion can we draw from the contrast between these two companies?

The rule of 40 portrays Gentrack as a more appealing business, therefore, a potentially more inviting investment.

Both of them are delivering good growth, but one of them has got the margins too, and the other doesn’t.

The obvious next question becomes; Sure, but is this already priced in the valuations?

Looking very quickly at their respective valuations, I’m not so sure that it is. In the next post in this series of tools, we will look at applying the rule of 40 to valuation metrics.

Conclusion

Hopefully you’ve seen today that the rule of 40 is useful as a metric to track overtime to get a high-level view of a company’s performance.

Running through the numbers provides the simple observation that meeting the Rule of 40 is actually quite difficult; only a small few, very special (and potentially very promising) companies will be able to constantly score around or above 40 for years.

These businesses are likely very interesting to look at.

Over time, we also note that companies become very interesting when they transition from the investment phase (cash flow burning with big negative margins) to scaling-up phase (approaching cash flow breakeven with high growth rates). This tends to correlate to them looking more attractive on the Rule of 40.

Three last quickfire points:

We can’t make a decision based on the rule alone. Always combine number with story.

Things can turn quickly when companies are growing fast and moving in the right direction towards positive cashflows.

When in doubt, tune in later.

What do you think?

Disclaimer

The content and data on this website is for information purposes only, and should not be read as investment advice, or advice on tax or legal matters. The companies and strategies discussed are on the site for entertainment only, we may or may not at any time be invested in the companies, and may be referencing companies simply as examples, ideas or for discussion.

By viewing the contents of this article, you agree:

(1) you have read and understood the warning and disclaimer above;

(2) not to make any decision based on the contents of the article;

(3) not to place any reliance on the contents of the article; and

(4) that the author is not responsible or liable, directly or indirectly, in any way for any loss or damage of any kind incurred as a result of, or in connection with, your use of, or reliance on, any of the contents of these articles.

👏🏼👏🏼 great to see the comparisons and the adjustments you added. Nicely done mate.